Representing suffering—how to do it, when we should do it at all—has long been a subject of debate. At the center of that debate is the role of the audience: how do we, as readers and viewers, witness depictions of violence in images, films, plays, or literature?

In On Photography, Susan Sontag suggests that the act of looking, from a distance, is self-regarding. For writer and photographer Teju Cole, this visual and affective act is limited in what it can connote. Joining Sontag in conversation, Cole argues in Black Paper that the visual illustrates without condemning, becoming a collection of violence for consumption. But he ultimately concludes that in many ways, bearing witness to the existence of this suffering is better than ignoring its reality.

In On Photography, Susan Sontag suggests that the act of looking, from a distance, is self-regarding. For writer and photographer Teju Cole, this visual and affective act is limited in what it can connote. Joining Sontag in conversation, Cole argues in Black Paper that the visual illustrates without condemning, becoming a collection of violence for consumption. But he ultimately concludes that in many ways, bearing witness to the existence of this suffering is better than ignoring its reality.

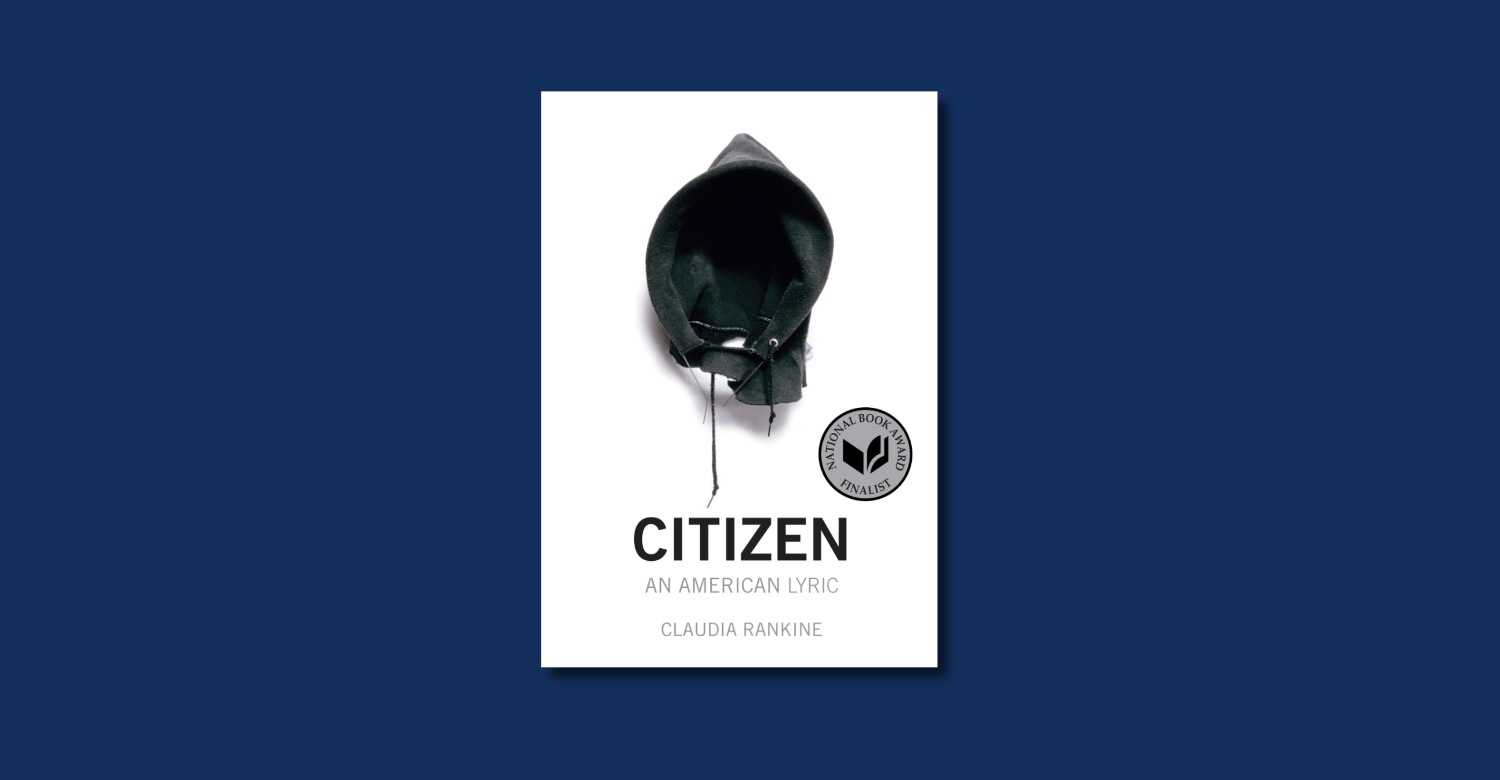

Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric—a hybrid work of poetry, prose, and visual art—boldly considered these questions, and many others, through its use of language and form. Recounting a series of mounting racial slights and aggressions, endured in daily life and in the media, the book has proven both prescient and timeless. Upon its release, the book spoke to a particular moment: it was published in October 2014, just months after the murders of Eric Garner and Michael Brown at the hands of white policemen, which led to protests and unrest across the country and the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement.

As descriptions and scenes of police brutality and racist violence were being broadcasted on the national scale, Citizen intimately considered subtler, everyday racist encounters through language and image. Six years later, in 2020, as demonstrations spread nationwide following the murder of George Floyd, also by white police, the book had a resurgence, landing on numerous reading lists circulated by institutions and major news outlets to contextualize the moment at hand. Today, on the tenth anniversary of its publication, the book still feels as urgent as ever.

Citizen’s hybrid form makes it difficult to categorize. It was the first and only book to be nominated for the National Book Critics Circle Award in multiple categories: poetry, which it won, and criticism. But this hybridity also allowed the book to become a living memorial, as each successive reprint adds to the list of names of victims of police brutality found on page 134. These updates are a stark reminder of the unceasing violence of the last decade, as well as the continued relevance of the book’s content.

At the heart of Citizen is the question of what it means for language to articulate experiences of racism that cannot be simply explained, and to address another without the capacity to hear. “How difficult is it for one body to feel the injustice wheeled at another?” Rankine writes. “Are the tensions, the recognitions, the disappointments, and the failures that exploded in the riots too foreign?”

At one point, Rankine overhears someone ask Judith Butler “what makes language hurtful.” Rankine paraphrases Butler’s response:

Our very being exposes us to the address of another, [Butler] answers. We suffer from the condition of being addressable. Our emotional openness, [Butler] adds, is carried by our addressability. Language navigates this.

Rankine begins to consider her own “addressability,” and the ways in which she is “rendered hypervisible in the face of” racist language. “Language that feels hurtful is intended to exploit all the ways that you are present,” she writes. “Your alertness, your openness, and your desire to engage actually demand your presence.”

At another point, Rankine cites Ralph Waldo Ellison, raising the central concern of her work: “Perhaps the most insidious and least understood form of segregation is that of the word.” The vignettes that populate Citizen are rendered by simple expressions and passing comments—what we’d call microaggressions—that evince and undergird structural racism. In these moments, the experience of language becomes a force that separates understandings along lines of race.

Rankine’s vignettes create a poetics of uncomfortable encounter. Across the text, she illustrates many failed discursive encounters between Black and white Americans. But she also produces the potential for encounter directly with her reader, through the constant address of the “you.” In depicting microaggressions in and through language, Rankine employs this direct address to push readers to think through racism in its subtlest forms.

At one point, Rankine writes about an encounter in the grocery store. The cashier wants to know if “your” card will work, she writes, but he didn’t ask the friend that checked out just prior. “As she picks up her bag, she looks at you to see what you will say,” Rankine writes of the friend. “She says nothing. You want her to say something—both as witness and as a friend. She is not you; her silence says so.” Here, “you” directs the reader’s focus on not just the racist slight against the speaker, but the place of the silent bystander as well.

In a similar encounter, after being in line at the drugstore, a man walks in front of “you” in line. The cashier says that “you” were next. Rankine separates the lines that follow into prose-like verses: “Oh my God, I didn’t see you. / You must be in a hurry, you offer. / No, no, no, I really didn’t see you.” Here, the “you” serves multiple purposes, referring to the subject of the microaggression, the man in line, and the reader—a sly collapse in address. As Lauren Berlant noted in a 2014 conversation with Rankine, “We are left there with the atmosphere of encounter pressuring a disturbance in us.”

Over and again, Rankine repositions who is being called upon or called out. She repositions white readers of the book, but simultaneously denies them direct contact. Through this denial, she demonstrates the failure of address built upon white ignorance, by using the paradoxical second person address throughout her poetic form. The discomfort produced from being addressed is the result of this problem of address, but also becomes the possibility for conveying the experience of racism—to those who have never considered this reality.

In the introduction of her 2019 play The White Card, Rankine details an exchange that occurred during a question-and-answer session that followed her reading from Citizen, demonstrating the varying impact of this “you.” A white man from the audience, eager to be prescribed an anti-racist regimen, asked Rankine, “What can I do for you?” Rankine responded, “The question you should be asking is what you can do for you.” Rankine uses this “you” to demonstrate how many white Americans, like this audience member, have situated themselves outside of the everyday racist encounters that populate Citizen.

In the introduction of her 2019 play The White Card, Rankine details an exchange that occurred during a question-and-answer session that followed her reading from Citizen, demonstrating the varying impact of this “you.” A white man from the audience, eager to be prescribed an anti-racist regimen, asked Rankine, “What can I do for you?” Rankine responded, “The question you should be asking is what you can do for you.” Rankine uses this “you” to demonstrate how many white Americans, like this audience member, have situated themselves outside of the everyday racist encounters that populate Citizen.

Citizen’s direct address, its you, implicates the reader, turning the text into a conversation. As Rankine said in a recent discussion about her 2020 book Just Us, “There’s no conversation without the other.” In breaking silences and forcing encounters, Citizen reveals how the only way out is through language.