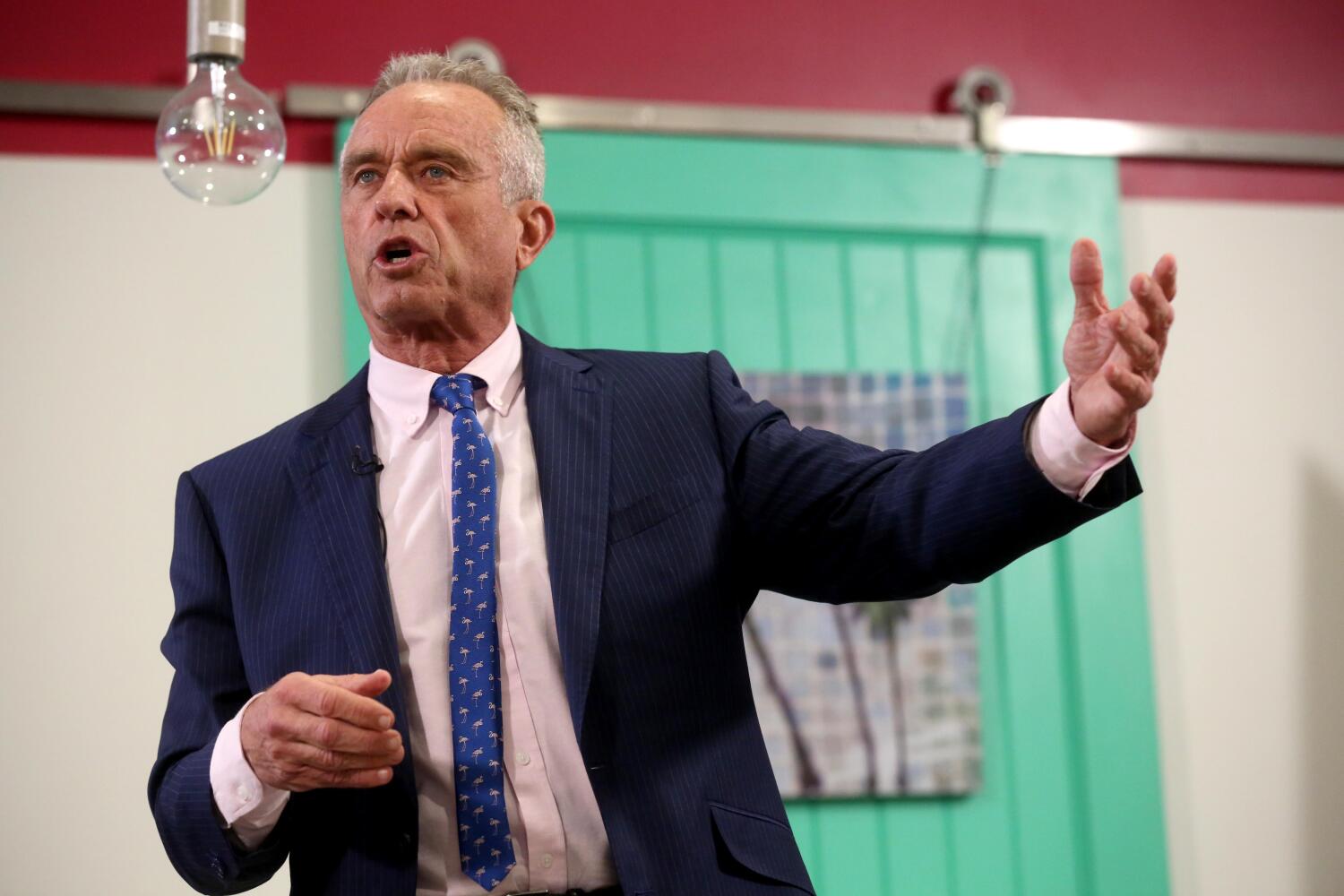

There was a time before the turn of the millennium when Robert F. Kennedy Jr. gave a full-throated accounting of himself and the things he cared about. He recalls his voice then as “unusually strong,” so much so that he could fill large auditoriums with his words. No amplification needed.

The independent presidential candidate recounts those times somewhat wistfully, telling interviewers that he “can’t stand” the sound of his voice today — sometimes choked, halting and slightly tremulous.

The cause of RFK Jr.’s vocal distress? Spasmodic dysphonia, a rare neurological condition, in which an abnormality in the brain’s neural network results in involuntary spasms of the muscles that open or close the vocal cords.

“I feel sorry for the people who have to listen to me,” Kennedy said in a phone interview with The Times, his voice sounding as strained as it does in his public appearances. “My voice doesn’t really get tired. It just sounds terrible. But the injury is neurological, so actually the more I use the voice the stronger it tends to get.”

Since declaring his bid for the presidency a year ago, the 70-year-old environmental lawyer has discussed his frayed voice only on occasion, usually when asked by a reporter. He told The Times: “If I could sound better, I would.”

SD, as it’s sometimes known, affects about 50,000 people in North America, although that estimate may be off because of undiagnosed and misdiagnosed cases, according to Dysphonia International, a nonprofit that organizes support groups and helps fund research.

As with Kennedy, cases typically arise in midlife, though increased recognition of SD has led to more people being diagnosed at younger ages. The disorder, also known as laryngeal dystonia, hits women more often than men.

Internet searches for the condition have spiked, as Kennedy and his gravelly voice have become regular staples on the news. When Dysphonia International posted an article answering the query, “What is wrong with RFK Jr.’s voice?,” it got at least 10 times the traffic of other items.

Those with SD usually have healthy vocal cords. Because of this, and the fact that it makes some people sound like they are on the verge of tears, some doctors once believed that the croaking or breathy vocalizations were tied to psychological trauma. They often prescribed treatment by a psychotherapist.

But in the early 1980s, researchers, including Dr. Herbert Dedo of UC San Francisco, recognized that SD was a condition rooted in the brain.

Researchers have not been able to find the cause or causes of the disorder. There is speculation that a genetic predisposition might be set off by some event — physical or emotional — that triggers a change in neural networks.

Some who live with SD say the spasms came out of the blue, seemingly unconnected to other events, while others report that it followed an emotionally devastating personal setback, an injury accident or a severe infection.

Kennedy said he was teaching at Pace University School of Law in White Plains, N.Y., in 1996 when he said he first noticed a problem with his voice. He was 42 years old.

His campaigns for clean water and other causes in those days meant that he traveled the country, sometimes appearing in court, sometimes giving speeches. He lectured, of course, in his law school classes and even co-hosted a radio show. Asked if it was hard to hear his voice gradually devolve, Kennedy said: “I would say it was ironic, because I made my living on my voice.”

“For years people asked me if I had any trauma at that time,” he said. “My life was a series of traumas so … so there was nothing in particular that stood out.”

Kennedy was just approaching his 10th birthday when his uncle, President John F. Kennedy, was assassinated. At 14, his father was shot to death in Los Angeles, on the night he won California’s 1968 Democratic primary for president.

RFK Jr. also lost two younger brothers: David died at age 28 of a heroin overdose in 1984 and Michael died in 1997 in a skiing accident in Aspen, Colo., while on the slopes with family members, including then-43-year-old RFK Jr.

It was much more recently, and two decades after the speech disorder first cropped up, that Kennedy came up with a theory about a possible cause. Like many of his other highly controversial and oft-debunked pronouncements in recent years, it involved a familiar culprit — a vaccine.

Kennedy said that while he was preparing litigation against the makers of flu vaccines in 2016, his research led him to the written inserts that manufacturers package along with the medications. He said he saw spasmodic dysphonia on a long list of possible side effects. “That was the first I ever realized that,” he said.

Although he acknowledged there is no proof of a connection between the flu vaccines he once received annually and SD, he told The Times he continues to view the flu vaccine as “at least a potential culprit.”

Kennedy said he no longer has the flu vaccine paperwork that triggered his suspicion, but his campaign forwarded a written disclosure for a later flu vaccine. The 24-page document lists commonly recognized adverse reactions, including pain, swelling, muscle aches and fever.

It also lists dozens of other less common reactions that users said they experienced. “Dysphonia” is on the list, though the paperwork adds that “it is not always possible to reliably estimate their frequency or establish a causal relationship to the vaccine.”

Public health experts have previously slammed Kennedy and his anti-vaccine group, Children’s Health Defense, for advancing unsubstantiated claims, including that vaccines cause autism and that COVID-19 vaccines caused a spike of sudden deaths among healthy young people.

Dr. Timothy Brewer, a professor of medicine and epidemiology at UCLA, said an additional study cited by the Kennedy campaign to The Times referred to reported adverse reactions that were both unverified and extremely rare.

“We shouldn’t minimize risks or overstate them,” Brewer said. “With these influenza vaccines there are real benefits that so far outweigh the potential harm cited here that it’s not worth considering those types of reactions further.”

Anyone with concerns about influenza vaccine side effects should consult their physician, he said.

So what does research suggest about SD?

“We just don’t know what brings it on,” said Dr. Michael Johns, director of the USC Voice Center and an authority on spasmodic dysphonia. “Intubation, emotional trauma, physical trauma, infections and vaccinations are all things that are incredibly common. And it’s very hard to pin causation on something that is so common when this is a condition that is so rare.”

No two SD sufferers sound the same. For some, spasms push the vocal cords too far apart, creating breathy and nearly inaudible speech. For others, like Kennedy, the larynx muscles push the vocal cords closer together, creating a strained or strangled delivery.

“I would say it was a very, very slow progression,” Kennedy said last week. “I think my voice was getting worse and worse.”

There were times when mornings were especially difficult.

“When I opened my mouth, I would have no idea what would come out, if anything,” he said.

One of the most common treatments for the disorder is injecting Botox into the muscles that bring the vocal cords together.

Kennedy said he received Botox injections every three or four months for about 10 years. But he called the treatment “not a good fit for me,” because he was “super sensitive to the Botox.” He recalled losing his voice entirely after the injections, before it would return, somewhat smoother, in the days that followed.

Looking for a surgical solution, Kennedy traveled to Japan in May, 2022. Surgeons in Kyoto implanted a titanium bridge between his vocal cords (also known as vocal folds) to keep them from pressing together.

He told a YouTube interviewer last year that his voice was getting “better and better,” an improvement he credited to the surgery and to alternative therapies, including chiropractic care.

The procedure has not been approved by regulators in the U.S.

Johns cautioned that titanium bridge surgeries haven’t been consistently effective or durable, with some reports of the devices fracturing, despite being implanted by reputable doctors. He suggested that the more promising avenue for future breakthroughs will be in treating the “primary condition, which is in the brain.”

Researchers are now trying to find the locations in the brain that send faulty signals to the larynx. Once those neural centers are located, doctors might use deep brain stimulation — like a pacemaker for the brain — to block the abnormal signals that cause vocal spasms. (Deep brain stimulation is already used to treat patients with Parkinson’s disease and other afflictions.)

Long and grueling presidential campaigns have stolen the voice of many candidates. But Kennedy said he is not concerned, since his condition is based on a neural disturbance, not one in his voice box.

“Actually, the more I use the voice, the stronger it tends to get,” he said. “It warms up when I speak.”

Kennedy was asked if the loss of his full voice felt particularly frustrating, given his family’s legacy of ringing oratory. He replied, his voice still raspy, “Like I said, it’s ironic.”