Ballinger‘s Kate Hallinan shares the important ways the workplace should embrace inclusivity through mindful design.

Imagine walking into a building where every detail, from the height of the counters to the brightness of the lights, feels just right for you. Now imagine the opposite – tight corners, illegible wayfinding and the unshakeable feeling that a space isn’t for you.

Inclusive design rejects the idea that spaces narrowly define their users, resulting in projects attuned to a wide range of human abilities. The goal of inclusive design is to go beyond the functional minimums and create spaces that allow for an equitable experience for all users.

Currently, Ballinger is part of team ensuring that a major pharmaceutical company’s workspaces embody inclusive design practices and provide an equitable experience for all employees. The most important element of this process involves recognizing and reflecting on the variety of human experiences.

The Spectrum of Human Experience

Acknowledging the difference between equality and equity is a key component of inclusive design. Equal assumes each person starts with the same level of ability, the same lived experience that informs their relationship to space, and the same tolerance for environmental factors. Equitable design understands that human experiences are varied, and people often need different tools to have the same opportunities and achieve the same level of success.

How varied is the human experience? The CDC estimates that up to 1 in 4 adults in the United States are living with some type of disability. This includes mobility, cognitive, vision, hearing and other difficulties that prevent self-care and independent living. Not included in this number is the percentage of people that — due to illness, injury, trauma or distress — may not be functioning at a day-to-day level that would be considered “average.”

Numerous disabilities are not visually apparent and, in the workplace, only about 4.5% self-identify as living with a disability to their employer. We are constantly moving through spaces in partnership with people experiencing challenges that aren’t allowing them the same sense of independence, ease and safety as the people around them.

Real-World Application

Nothing about us without us.

This powerful slogan from disability rights groups underscores the importance of involving the people directly affected by design decisions. Inclusive design thrives on diversity of input, ensuring that those facing the most barriers have a voice in the process.

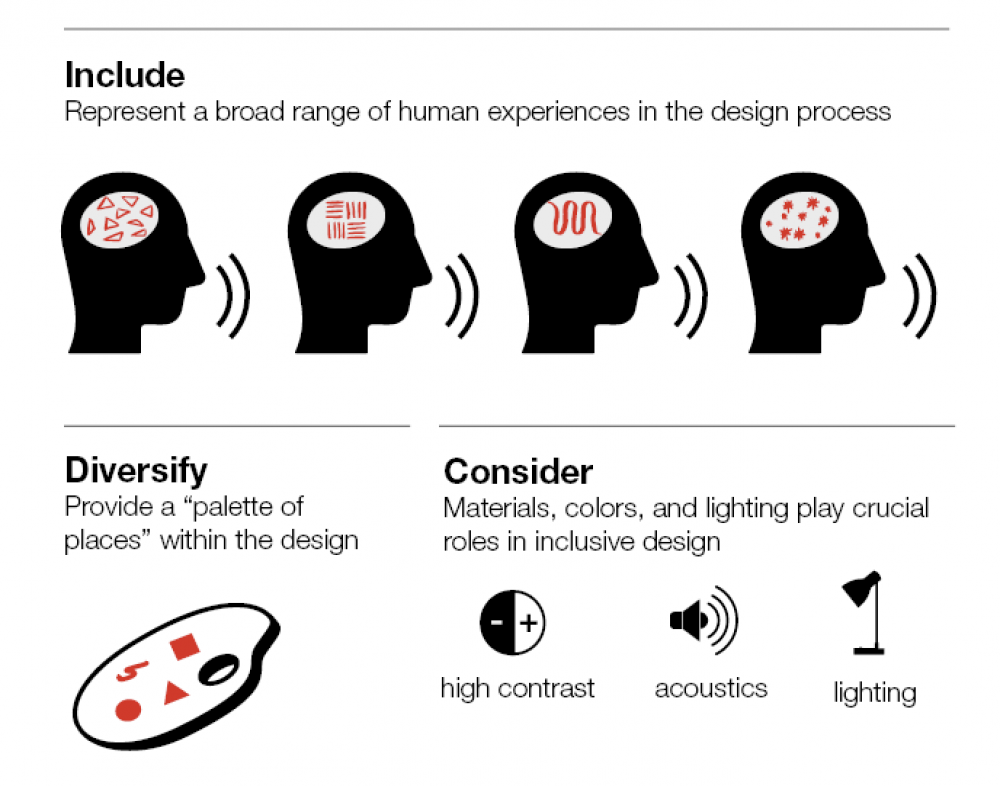

The first step to understanding how to design a more inclusive space is to ensure users who represent a broad range of human experiences have a say in the design process. As we set up user meetings and focus groups, engaging the users who face the most barriers to success and have the greatest need for spaces that promote inclusivity is a priority in our process. Having that diversity of experience will help us understand the broader design challenges that we need to solve.

Creating inclusive spaces often means balancing competing needs. For example, a space must cater to both sensory-seeking and sensory-defensive individuals, providing both connection and protection, flexibility and predictability. This can be achieved through a “palette of places” approach, offering various settings within a larger environment to meet different needs.

Organizing these settings into intuitive and predictable zones or “neighborhoods” allows users to easily orient themselves within the larger space and navigate to spaces that they feel most supported. Specialty and amenity spaces can be used to connect these spaces, creating landmarks to further define these neighborhoods and reinforce wayfinding.

Neighborhoods can also be used to both foster community and give the individual a sense of ownership and control. For example, a neighborhood assigned to a department or team becomes a zone to collaborate with direct counterparts, see and be seen by managers, and display department artifacts and shared values. That same neighborhood narrows down options for an employee by distilling the larger workplace into a more manageable size, provides individual storage for that employee, and can include space types or tools unique to that employee’s way of work.

Materials, colors and lighting play crucial roles in inclusive design. High-contrast colors help visually impaired users navigate spaces safely. Specific colors can create either an active or calming atmosphere. Texture and contrast enhance experiences for those who perceive color differently. Lighting can guide users through spaces and acoustical treatments benefit both hearing-impaired individuals and those needing a quieter environment. On their own, any of these space-defining and wayfinding strategies would be successful for a large percentage of users. By utilizing multiple methods, you are ensuring a more inclusive experience.

Inclusive Design Matters

Despite progress, the stigma around disability persists. Many perceive disabilities as barriers to productivity, overlooking the unique strengths and perspectives these individuals bring. A recent survey highlighted in the Harvard Business Review revealed that 80% of C-suite executives and their direct reports who have disabilities are not disclosing them, likely due to fears of discrimination. Inclusive design reduces the need for special accommodations, signaling to all users that they are welcome, valued and included.

Research consistently shows that diversity leads to better decision-making, higher-quality work and greater team satisfaction. Employees with disabilities often demonstrate higher efficiency, lower absenteeism and greater loyalty. Inclusive design not only removes barriers but also enriches workplaces with diverse talents and perspectives.

The Future of Inclusive Design

Post-COVID, employees value engagement, culture, well-being and work-life balance over pay and benefits. Inclusive design addresses these needs by creating flexible, supportive spaces that accommodate a wide range of human experiences.

No longer is a “one-size-fits-all” approach acceptable.

As designers, our greatest challenge is overcoming the limitations of our own perspectives. By embracing diverse input and making inclusion a rule from the start, we can create stronger, more equitable spaces that truly serve all users. Ultimately, inclusive design is not just about meeting minimum standards — it’s about striving for spaces that celebrate and accommodate the full spectrum of human experience, making room for everyone.