Join our daily and weekly newsletters for the latest updates and exclusive content on industry-leading AI coverage. Learn More

The Chips & Science Act was a bipartisan law passed to provide $52 billion for the U.S. semiconductor industry. It was created in the name of ensuring national security and a secure supply chain for critical electronics goods at a time when relations with China were frosty.

The act became law in part because it promised to bring high-value jobs back to the United States, decades after those jobs left for low-cost areas in Asia. But Donald Trump is president-elect now and the Republicans are firmly in control of the federal government. We’ll soon find out if the love for electronics, chips and the jobs they bring is still there.

Under Trump, new leaders have been tapped such as Vivek and Elon Musk to cut government spending via the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE). Will they continue to support the Chips & Science Act? And do they see the value of investing in semiconductor factories further with a second act to finish the job of completing the chip factories that have been started?

To answer these questions, I did an interview with Scott Almassy, a partner with consulting and accounting firm PwC. He has been running the company’s semiconductor practice for a long time during his 20-year stint at PwC. For that job, he has had to stay on top of the intricacies of the chip business, not only from the view of Silicon Valley but also in places like South Korea.

Here’s an edited transcript of our interview.

VentureBeat: Could you start with some of your background?

Scott Almassy: I’m a partner with PwC. Obviously we’re one of the large accounting and advisory firms. I’ve been here 20 years. Currently I’m our U.S. semiconductor leader. Our business is split between audit and advisory, audit being assurance, public companies, capital markets, audit opinions, and then advisory is consulting. I sit over both of those, but I’m an audit partner by background. In my 20 years I’ve been in the U.S., mostly in Silicon Valley, and also South Korea for three years. Virtually all my clients have been semiconductor companies, from foundries to the fabless guys at the end, putting the final products out there. I’ve seen the end to end throughout my career.

As far as perspectives go, our industry has–especially starting with COVID, it’s been quite in the spotlight. Now everyone is curious about shifts, about the industry. You have the CHIPS Act. You have China. You have the rest of the world trying to onshore, reshore, whatever you want to call it. At the same time you still have the 30-plus years of muscle memory for Asia, moving everything there. Now people are figuring out how to bring it back and/or diversify.

VentureBeat: There was bipartisan support for the CHIPS Act. That’s why it passed. Where does it stand after the election in terms of what might be modified about it, or whether the money that’s there is going to get spent or allocated or not?

Almassy: A number of different perspectives. You’re right that it was bipartisan. In theory it would be harder to unwind, not only from an administrative perspective, but a political and emotional perspective. You have a number of states that were super excited that that funding was rolled out and large players would build in their states. That makes it difficult to unwind. Initially, and obviously we’re only seven days past it–initially there was a bit of consternation. Are the funds going to get doled out? Some folks, including potentially Commerce, who’s in charge of giving the money out, want to make sure they dot all the Ts and cross the Is. Whether they needed to expedite that, whether the companies that were granted the money needed to work together to get that across the finish line and locked in before the change in administration.

At least what I’ve heard and what I’ve read recently is that the initial CHIPS Act – the $51-52 billion, whatever number in pure cash, and then the tax incentives would take it higher – probably isn’t at risk. That money will continue to be doled out. An interesting thing to watch might be–I don’t know how familiar you are with the CHIPS Act, but effectively the money was earmarked, the $50 billion plus. Commerce then set out to figure out what it would look like and what they wanted people to do before they gave them the money. That whole thing was almost a clean sheet. Trying to figure out, is it limited on how you can expand in China? Or not necessarily China, but countries on the list. One thing to watch out for is if these contracts are signed prior to the new administration coming, the money might still get doled out, but do they try to put additional restrictions on it, put a spin on it?

I’m not sure there can be wholesale changes. It’s not restrictive. But the terms are written with preventing China’s growth in mind, making sure jobs are made, making sure you’re not doing buybacks. All that stuff is already in there.

VentureBeat: The other piece of the picture that seems new is the likelihood of tariffs happening. If there’s still a supply chain that exists outside the U.S. and they supply parts into the semiconductor factories, are the costs going to go up for that reason? People were pointing out things like the cost of game consoles. A PS5 Pro costs $700 now, and it might go to $1,000 if it’s affected by tariffs. That’s something that is manufactured in China. AMD is the key supplier on that. But I don’t know which pieces of that are going to be affected by tariffs, if any.

Almassy: It’s an interesting point on tariffs. Your numbers are accurate. If a piece of technology–let’s say it’s entirely fabricated outside the U.S. It’s ultimately imported into the U.S. as a completed console or phone or whatever it is. The price point on those things–I’m not going to say it’s price inelastic, but the demand tends to be there because the products are expensive as it is. I don’t know what the right number is, but barring a 100% tariff that doubles that to $1,500, I get the sense–I don’t have empirical evidence, but anecdotally, with tariffs in Trump 1, China just passed those on from the high end. Where you really start to get the impact is on the materials, the commodities, the steel and aluminum, the things that really go into the beginning of supply chains that build things that aren’t $500, $600, $700.

My perspective, tariffs may very well become a thing. But when you talk about a supply chain that’s outside the U.S. and the ultimate finished product comes in, maybe there’s a combination of passing some costs on to the consumers and absorbing a bit of it into margin. But I’m not sure it will have a huge impact on, one, company behavior, and two, consumer behavior, or three, the general supply chain. If you look at a lot of the things that are coming into the U.S. from a semiconductor perspective that are not these consoles, these finished products, or selling to OEMs and ODMs–it’s a lot of things that end up in data centers or AI-type things. Cutting-edge places where you may not necessarily be deriving a product from it, but it’s almost a service. You can layer that in with an additional 10 cents per hour or whatever cost, if you’re one of the large guys with pricing power.

VentureBeat: What’s the state of the chip industry in terms of sales? I saw the SIA’s November 5 report. It said semiconductor sales were up 23% in Q3. As these things are happening, what’s your view of how healthy the global chip industry is right now?

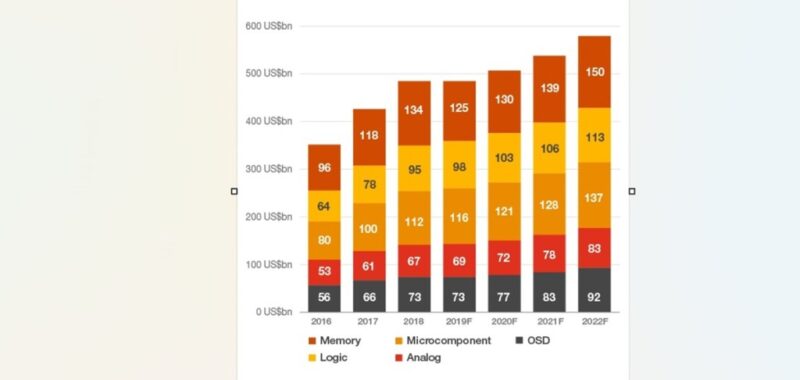

Almassy: I do think it’s a healthy industry at the moment. There was an apex back in 2021, 2022. You get these incredibly high numbers. We were sub-$500 billion globally, and then you shoot up close to six, and then drop back down. There was that overbuying, double buying, triple buying, whatever you want to call it. There was a bit of absorption.

The industry recently was buoyed a little bit – or a lot, depending on how you want to frame it – by AI. But underneath that, you have a number of different sub-sectors that are rebounding at different paces. Memory is recovering a bit. Even within memory you have the standard DRAM that runs the simplest of devices, all the way up to the high-bandwidth that runs these AI models. That’s started to recover. You see that a bit in the results of Samsung and Hynix and Micron. As far as the handset makers go, there was a bit of a blip in China a few years ago. That seems to be starting to recover.

Generally my sense is that the industry is healthy. The numbers month to month have been trending quite well. It doesn’t surprise me that quarterly you’re over 20% higher. I’m not sure that will sustain itself for the next 12 months, but I do think growth is in the cards. Maybe high single digits. You have different aspects of the industry coming back at different levels. Overhanging it all you have auto, which seems to be a long-term growth vector for many years. It continues to be many years down the road. It’s a generally healthy industry. But it is cyclical.

VentureBeat: Along with these revenue numbers, getting back to the U.S., are we starting to see more jobs in the U.S. coming because of construction from the CHIPS Act?

Almassy: Definitely construction jobs. In the grand scheme of labor it’s not significant, but there are thousands of jobs required to build these factories from a construction perspective. That’s been good. Once those are up and running, there will be jobs for folks needed to run the fabs, run the buildings, run everything that requires a specialized skill set that may be lacking in the U.S., because it’s not something that’s been focused on. That will be interesting. You have the construction jobs now, and then once they’re in production, will there be enough bodies with the requisite skill set? We’ve heard of TSMC sending some of their folks to Phoenix as an example. But how sustainable is that to get this off the ground?

It’s definitely spurring the economy, spurring jobs. A number of projects were already in play when the CHIPS Act was finalized. They had started these projects in anticipation of getting the funding. But then you had a few more announced once the funding was finalized. Jobs are there. For years, the U.S. has pushed more toward design and cutting edge, going through the R&D, as opposed to manufacturing. It’s naive to think that overnight, or over the course of a couple of years, we’ll immediately reactivate that muscle memory. But it’s going to be necessary.

VentureBeat: Is there any good way of measuring how that progress is going? Whether in terms of people graduating in these areas and moving into the industry, or–that’s probably a big question. Is the supply base there to surround these factories?

Almassy: Exactly. Initial enrollment numbers this year and next year–if people see that this is something that the U.S. is taking seriously, they can say, “I’ll get my degree to coincide with when these buildings are up and running.” We wrote a point of view–this was back during the supply chain shortage. What can companies do to try to mitigate the potential downsides? Part of it is cooperation between companies and universities. Asia does that really well. Taiwan does that. When these companies go into these new territories, whether Ohio or Arizona, do they try to partner with universities, things like that, where you’re getting a work force that’s been trained in your processes for four years? Again, those don’t happen overnight either. To your point, I do think you measure it by enrollment, and then you measure it by those who stay through to graduation. It’ll be interesting.

VentureBeat: Are we expecting global demand to be good for when these things come online?

Almassy: Generally yes, but I do think it will be interesting, because as I said, it’s an incredibly cyclical industry. I don’t believe that there’s ever been this significant a proposed increase in capacity globally. Now, with that being said, the semiconductor industry now looks a lot different than it did in the past, when it was basically just computers. As went the computer, or as went the mobile phone, so went the industry. There are enough different sub-markets, if you will, that demand will stay strong. I do think there will be places for that capacity to go. I’ll put it that way.

Do I think that we’ll get to a point where the fabs are fully utilized, such that we’re in another place where there’s nowhere to go and prices can go up, though? I don’t think so. What it will do, I think, is allow people to reassess their supply chain and where they want to source things for different products and different manufacturing lines.

VentureBeat: I suppose people are going to want to relitigate this. “Hey, it’s a different administration. Now we want to see whether we’re really getting our money’s worth.” What do you see as the pros and cons now, if they’re any different than what they might have been before?

Almassy: For the existing one that was passed, I don’t see much difference. There were already a lot of guardrails in there, particularly because it was a big amount of money. It was the first program that went out. Obviously the Inflation Reduction Act followed, and that has a trillion-dollar price tag. That’s infrastructure and broader things that maybe people will see every day. But they wanted to make sure they weren’t just burning $51 billion.

I don’t know if they’ll relitigate it. I don’t know what would have happened if Harris had continued on. But I imagine that 2.0 would have been in the cards in some way, shape, or form. When that $50 billion was earmarked, that only represented about 20% of the cost of the projects that were in flight at the time. Something else would have had to happen. You know how lobbying goes. Chuck Schumer’s a big proponent of all that. I would imagine the chances of a CHIPS 2.0 are probably less at this point, just given, at least initially, the priorities laid out by Trump. Again, who knows? Do they go public-private partnership? Do they take companies and say, “You’re a buyer from this fab, put some money in”? But I don’t think we’ll see a CHIPS 2.0 where they say, “Here’s X billions to continue to grow.”

VentureBeat: The basic argument is that it’s an unstable world and this is a strategic industry, so it should be within our borders, as well as providing a lot of jobs, the kind of jobs that we want. That argument still seems the same.

Almassy: Absolutely. It’s just a matter of how you play to that message. Obviously there will be the China discussions. At the same time, if you take a step back, the fab, the front end, is only one part of the supply chain. There’s also some money allocated in the CHIPS Act for advanced packaging, which in the simplest of terms–previously you took a die, put it on a small chip, and you sell that one chip. Now you’re putting three, four, five, six together. They want to do that too.

At the same time, it’s 30 or 35 years of head start for Asia. If you’re honest with yourself as an administration, you want to reshore. You want it in our borders. You want national security. You want all of that. But it’s unrealistic for any sovereign nation to think they can get an end to end industry there. You have to weigh the pros and cons. What aspects do we want to ensure we own so we can hold some or most of the cards? What are we okay not bringing on shore, because the cost outweighs the benefit that we’d get? It’ll be interesting to see.

VentureBeat: AI is so much bigger now than it was when all of these plans were being conceived. You could have argued that semiconductors were the thing to invest heavily in with government support some years ago, but perhaps now people might say–if you had a choice between investing in AI or investing in semiconductors, what would you choose, and for what reasons?

Almassy: They’re not mutually exclusive. You need the semiconductors to invest in AI. I was talking about a cyclical industry. It’s almost the same cycle you had in the past. To your question, let’s say the answer that someone gives is, “Absolutely AI. We need to invest in AI. We need to own LLMs, because then we can monetize that data and be more efficient and so on.” Then 20 years down the road, “Oh man, wait, China and Taiwan still own all the stuff underneath that. If they decide to cut us off…” It’s funny if you look at it through that lens.

To your question, a number of people would probably say AI, of course. It’s new. But you still need the power to do that. If I’m a government, what would I want to invest in? You want to invest in bricks and mortar. A majority of the country relates to that. They see it. It’s tangible. But it is an interesting question. Where do you allocate your resources?

VentureBeat: It doesn’t sound like there’s been any new important signals communicated to this. We’re really waiting until January to find out.

Almassy: Exactly. It’ll be interesting to see what, if anything, they do in the lame duck session here. There was an announcement late last week–I don’t know what body it was, but they sent a note to the large equipment manufacturers putting them on notice that a significant amount of sales to China had been noted for the fabrication equipment. There are already sanctions and restrictions on cutting-edge things. ASML, the Dutch company, can’t sell certain things. Applied Materials, LAM, they can’t sell some of their higher-end stuff. But there’s still a lot that they can sell. A notice was sent last week saying, “Hey, we noticed this large percentage.” I don’t know if it’s an inquiry, but lame duck sessions can be a bit volatile.

I personally don’t think anything significant will happen at the last minute.

Names have started leaking out of potential candidates for various positions. We’ll start to see their leanings. Maybe that’s where we start to see whether there’s a tougher stance on China, or a move to a tougher stance on the Middle East. Saudi Arabia wants to get into the AI game. They want to do cutting-edge stuff. There have historically been mixed views, mixed relationships with the Middle East on a number of fronts. Where does this administration go with that? There are already heavy restrictions on China, which started under Trump and continued under Biden, but they’ve still demonstrated the ability to continue to grow their domestic knowledge and manufacturing. We’ll see.

Source link